My Favorite Literary Encounters: Raja Rao and Arun Kolatkar

In London in 1982, during a “Festival of India,” there was a gathering of many leading Indian writers - not R.K. Narayan, not Naipaul, but just about everyone else, or so I thought. This was the year after the publication of Midnight’s Children, so I was very much the new kid on the block, and was asked to deliver a talk about being a writer in the Indian diaspora. This talk eventually became the essay Imaginary Homelands, the title essay in my first collection of nonfiction.

It was an awe-inspiring gathering for a young writer to be part of. I remember that Mulk Raj Anand, author of Coolie, took a benevolent interest in me, and after that congress he started writing me letters of good advice, signed “Uncle Mulk.”

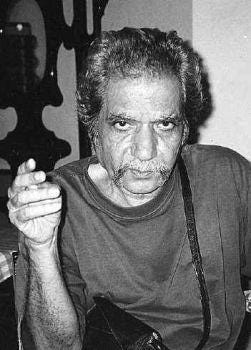

Perhaps the most enjoyable memory is of meeting and getting to know the great poet Arun Kolatkar. (If you haven’t read his book Jejuri, order it today!)

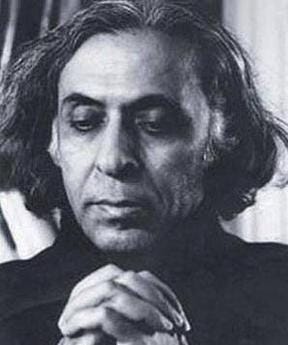

Arun was a mischievous spirit who had no time for pomposity. When Raja Rao, the eminent author of Kanthapura, began his talk by speaking for several minutes in Sanskrit and then saying, “Every educated Indian will understand what I have just said,” Arun responded with an amused, disapproving snort.

Later in his talk, Raja Rao spoke of the relationship between sound and silence, using, to make his point, what he called “the example of water.”

“Water without movement is what?” he asked, and then answered himself, “Is a lake.”

“Water with movement is what?” he next inquired, and responded, “Is a river.”

“Now - the water is still the same water. Only movement has been added,” he declared. “By the same token, sound is silence to which movement has been added.”

I had no real idea of what he was talking about. And then Arun Kolatkar, who was sitting next to me in the auditorium, whispered in my ear.

“Bowel, without movement, is what? -Is constipation! Bowel, with movement, is what? Is shit.”

In that instant I knew we were going to be friends.

Funny

So funny😂😂